Once you’ve grown food in your garden, one of the biggest challenges is finding a good way to preserve it. My two favorite ways are freezing and dehydrating. Since it’s spring, and I don’t have a lot growing in my garden to harvest at the moment, I decided to dehydrate a batch of ordinary mushrooms from the supermarket.

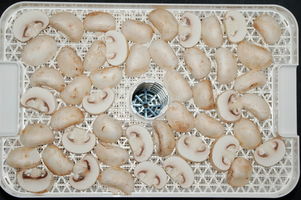

Here are the mushrooms before:

And the same mushrooms after:

I used about 2.5Kg of medium sized (about 5cm in diameter) mushrooms, which yielded about 1 liter of dried mushrooms. I sliced each mushroom into 3 or 4 pieces.

For mushrooms there are two things in particular to watch out for, making sure they don’t rot while you are drying them and making sure they are completely dried out. Since mushrooms will rot in warm humid conditions, you need to keep the temperature of the dehydrator low at the beginning until the mushrooms dry out a bit, then you can turn it up. You should also use a brush to clean them rather than running water, so you have as little dampness in the dehydrator to begin with. Finally, you need to leave them in the dehydrator until they are crispy and brittle. Just drying them until they are leathery is not good enough. It’s a good idea to check them 24 hours after drying them, to make sure they are really dry all the way through.

When dehydrating any food, keep in mind that it will shrink a lot. Even after rehydrating it will not return to it’s full original size. Always be careful not to cut it into pieces that are too small.

While mushrooms don’t need any pre-treatment before drying, most foods do. Most vegetables need to be blanched in boiling water or steam. Most fruits need to be treated with ascorbic acid (vitamin C). Some foods need to be treated with sulphur. For those of you reading this who already freeze their own foods, the blanching required for freezing vegetables is usually the same as what’s required for dehydrating them. Pre-treatment instructions will almost certainly come with your dehydrator, and can also be found by searching the Internet.

Blanching takes a little personal judgement. Blanching instructions usually say to time it starting when the water returns to a full boil. Often they say to be sure to add the food to the boiling water slowly enough so that it keeps boiling. If for example you have a 2.5Kg sack of potatoes, you will have to add it very slowly to even the largest pot of water for the water to keep boiling. If you add them that slowly, the potatoes you put in first will be sufficiently blanched long before you have added the last of them. You just have to experiment in such situations. In general it’s better to add everything to the water in one go, and start timing when the water starts boiling again, even if it takes a while for this to happen.

Only dehydrate top quality foods. Whatever you put in the dehydrator should be blemish free, fresh and free of dirt.

As a rule, the way to rehydrate any vegetable is to soak in hot water for 30 minutes, then use as you would fresh vegetables. Some things don’t always need so long, and often dehydrated vegetables can be added directly when cooking things like soup. One of my favorite ways to use dehydrated vegetables is added directly to ramen (instant noodles).

Besides mushrooms, some things I dehydrated recently are:

Carrots: 4-5mm slices work best. No pre-treatment is necessary. Grating them also works, but remember they will shrink a lot, so try to grate them as coarsely as possible.

Celeriac: 4-5mm slices work best. Blanch for about 3 minutes in boiling water or steam. Allow ample time for rehydration.

Potatoes: 4-5 mm slices. Blanch for 5 minutes in boiling water. Allow ample time for rehydration.

Onions: 4-5mm slices. No pretreatment necessary.

Green Beans: Cleaned and cut like normal. Blanch 3 minutes. You may have to experiment to get the blanching time right, it’s easy to over cook them.

Apples: Core and slice. Soak in a mixture of 1/4 tsp ascorbic acid and 250ml water (1 cup) for a few minutes before dehydrating. Limited shelf life.